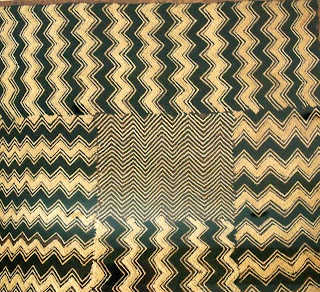

The Kuba tribes of the Democratic Republic of Congo, have been making their ceremonial cloth on simple wooden looms for the past four hundred years. Their weaving is considered to be among the highest forms of African art. In the past, the cloth was traded as currency. Today, these striking graphic textiles remain an important part of the culture of the Bumbal (people of the cloth) as dowry offerings, ceremonial costumes and burial rituals. According to their spiritual beliefs, the dead are dressed in raffia cloth so they can be recognized by their relatives in the next life.

Making the cloth is a collaborative effort by men and women of the same clan. The palm raffia is harvested by the men, and pounded while it is wet to achieve a fiber soft enough to be woven. Once the panels are completed, they are cut from the loom and the women embellish them with applique, patchwork and embroidery. Kuba cloth is made in small panels called Mbal, or long panels used for ceremonial skirts.

|

| Long panels can range up to thirty feet or longer |

There are hundreds of styles and sub-styles, but each panel is a unique interpretation based on colors and patterns of the region. It is the women who make the prized Kaisai velvet, or velour cloth. The design is stitched on the raffia and cut to form a dense velvet pile.

It was in the early 1900's when African traders brought the first Kuba cloth to the West. Artists such as Henri Matisse, Picasso and Paul Klee were inspired by the simple repetitive patterns and bold geometry of these vibrant works. By the late 1980's the supply coming out of the Congo had diminished.

|

| Photo courtesy of Woody Collin |